Miso is a staple of Japanese cuisine, but astronauts hoping to use the fermented soybean dish in space might need to adjust to a slightly different flavor.

An experiment aboard the International Space Station (ISS) has successfully produced miso paste, believed to be the first food intentionally fermented outside of Earth. This groundbreaking experiment could offer insights into the potential for life in space while also expanding the culinary options available to astronauts.

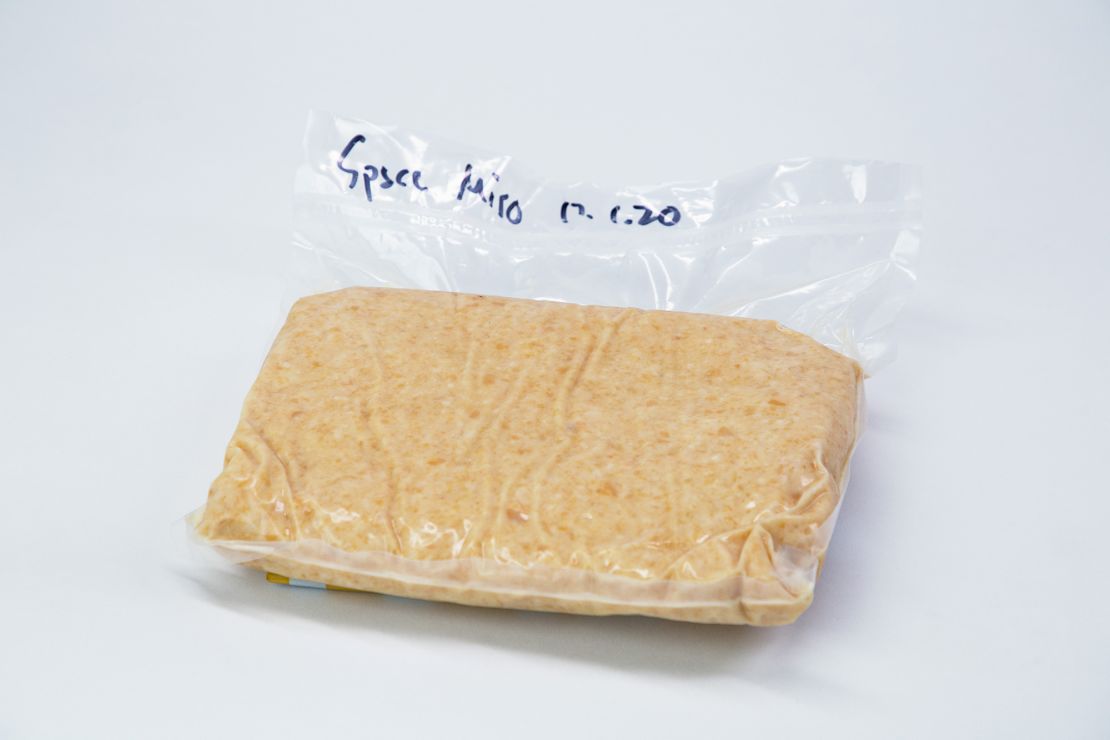

While the “space miso” shared the characteristic umami flavor of traditional miso, researchers noticed a distinct difference — it had a stronger roasted and nutty taste.

In March 2020, scientists Maggie Coblentz from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Joshua Evans from the Technical University of Denmark sent a small container of cooked soybean paste to the ISS. After 30 days of fermentation, it was returned to Earth as miso.

The miso was stored in a container equipped with sensors that closely monitored temperature, humidity, pressure, and radiation. According to a peer-reviewed paper published in the journal iScience on Wednesday, two additional batches of miso were fermented on Earth for comparison — one in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and the other in Copenhagen, Denmark.

“We didn’t know what to expect — fermentation had never been done in space before,” Evans, co-lead author of the study, told CNN.

“The space miso was darker and clearly more shaken up, which makes sense since it had traveled far more than the Earth-based miso. It was exciting to smell and taste the first bite.”

He explained that certain environmental factors in space, particularly microgravity and increased radiation, might affect how microbes grow and metabolize, which could in turn influence the fermentation process.

“By combining microbiology, flavor chemistry, sensory science, and broader social and cultural factors, our study opens up new avenues for exploring how life adapts when it moves to new environments like space,” Evans said.

He also noted that the research could “improve astronaut well-being and performance,” and “promote new forms of culinary expression, enhancing the diversity of culinary and cultural representation in space exploration as the field evolves.”

Miso, the salty fermented bean paste, is a key ingredient in many soups, sauces, and marinades, with each region of Japan having its own unique recipe.

Traditionally made from soaked soybeans, water, salt, and koji (a type of mold), miso usually takes about six months to develop its signature umami flavor, which intensifies over time.

Many fermented foods contain probiotics, live microorganisms that, when consumed, can support the good bacteria in the gut microbiome to help regulate digestion.

However, Evans emphasized that further analysis is needed to assess the nutritional value of the space miso, including its macromolecular composition and bioactive compounds.

Coblentz, also a co-lead author of the study, explained that the miso fermentation experiment aboard the ISS highlighted “the potential for life to exist in space,” demonstrating how a microbial community can thrive in such an environment.

Scientists have long experimented with growing and harvesting fresh produce in space, including various varieties of lettuce and radishes. In 2021, the ISS even hosted a taco party to celebrate the first harvest of chile peppers grown in space.

In another space-based culinary venture, Japanese company Asahi Shuzo, the maker of the popular Dassai sake brand, is brewing a special batch of sake fermented in space. The company has partnered with the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) for access to the ISS’s Kibo experiment module to conduct its tests.

Asahi Shuzo is also developing specialized space brewing equipment, with plans for its launch set for late 2025.