In 1934, an American team packed with the world’s best baseball players—Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Jimmie Foxx, and more—embarked on a barnstorming tour across Japan.

More than half a million Japanese fans gathered in Tokyo to welcome them before the team traveled from city to city, facing off against a squad of Japanese All-Stars. Eighteen games were played. The Americans won all 18.

Now, more than 90 years later, two more American teams—the Los Angeles Dodgers and the Chicago Cubs—have arrived in Japan for the season-opening Tokyo Series, beginning on March 18.

This time, however, the spotlight isn’t solely on the visitors. With stars like Shohei Ohtani, Yoshinobu Yamamoto, Roki Sasaki, Seiya Suzuki, and Shota Imanaga, many of the biggest names on the field aren’t here for a tour. They’re home.

More Than a Game

Baseball was introduced to Japan in the mid-to-late 1800s, but it wasn’t until 1896—when the first formal game between Japanese and American players took place—that the sport truly gained traction.

A team of students from Tokyo’s First Higher School, commonly known as Ichiko, faced off against a squad from the Yokohama Country and Athletic Club, composed of American businessmen, traders, and missionaries. That game marked the beginning of Japan’s deep and enduring love affair with baseball.

“Reporters from the national newspapers were present, marking a historic moment—this was the first time Japanese players were allowed on the grounds of the foreigners’ club,” Japanese baseball expert Robert Whiting told CNN Sports with a laugh.

“They played the game, and the Japanese won 29-4. It was a humiliating loss for the Americans. They demanded a rematch, claiming they hadn’t practiced enough. They lost again.”

The impact of the victory on Japan was later reflected upon by diplomat and future ambassador to the U.S., Tsuneo Matsudaira.

“The game spread like wildfire across the country,” he recalled in 1907. “Just months later, even children in remote primary schools far from Tokyo could be seen playing with bats and balls.”

According to Japanese baseball expert Robert Whiting, the significance of these games is deeply tied to the era of Sakoku—Japan’s period of feudal isolation, which had ended less than 50 years earlier.

“This was major national news,” Whiting told CNN. “It was a turning point that helped make baseball Japan’s national sport. The prevailing sentiment was that Japan had fallen behind the rest of the world due to its isolation, and baseball became a powerful symbol of modernization and progress.”

Just as Japan’s historical context shaped baseball’s popularity, it also influenced how the game evolved differently from its American counterpart.

Following the end of the Edo period in 1868, Japan underwent rapid modernization, sparking fears that the nation was losing its cultural identity. This led to the development of wakon yōsai—a philosophy of embracing Western ideas while maintaining a Japanese spirit. Baseball, like many other imports, was adopted but reinterpreted through a uniquely Japanese lens.

“Sports came from the West,” an Ichiko player once said. “But in Ichiko baseball, we weren’t just playing a game—we were infusing it with the spirit of Japan. Yakyu (baseball) became a way to express the samurai spirit.”

That mindset, according to Japanese baseball expert Robert Whiting, helped define the future of the sport in Japan.

“The majority of students at Ichiko came from samurai families, so they brought a martial arts mentality to their training,” Whiting told CNN. “In the U.S., baseball was a spring and summer sport. In Japan, it became a year-round commitment. If you played, you had to dedicate yourself completely.”

That relentless work ethic still defines the Japanese game today. According to Detroit Tigers pitcher Kenta Maeda, training expectations in Japan remain more intense than in the U.S.

“In Japan, spring training lasts much longer, and the drills are much tougher,” Maeda told CNN Sports through his interpreter, Daichi Sekizaki.

Japan’s First Golden Age

By 1944—just a decade after the American All-Star team toured Japan—baseball had become so deeply ingrained in Japanese culture that, during World War II, some Japanese infantry reportedly charged into battle shouting, “To hell with Babe Ruth!”

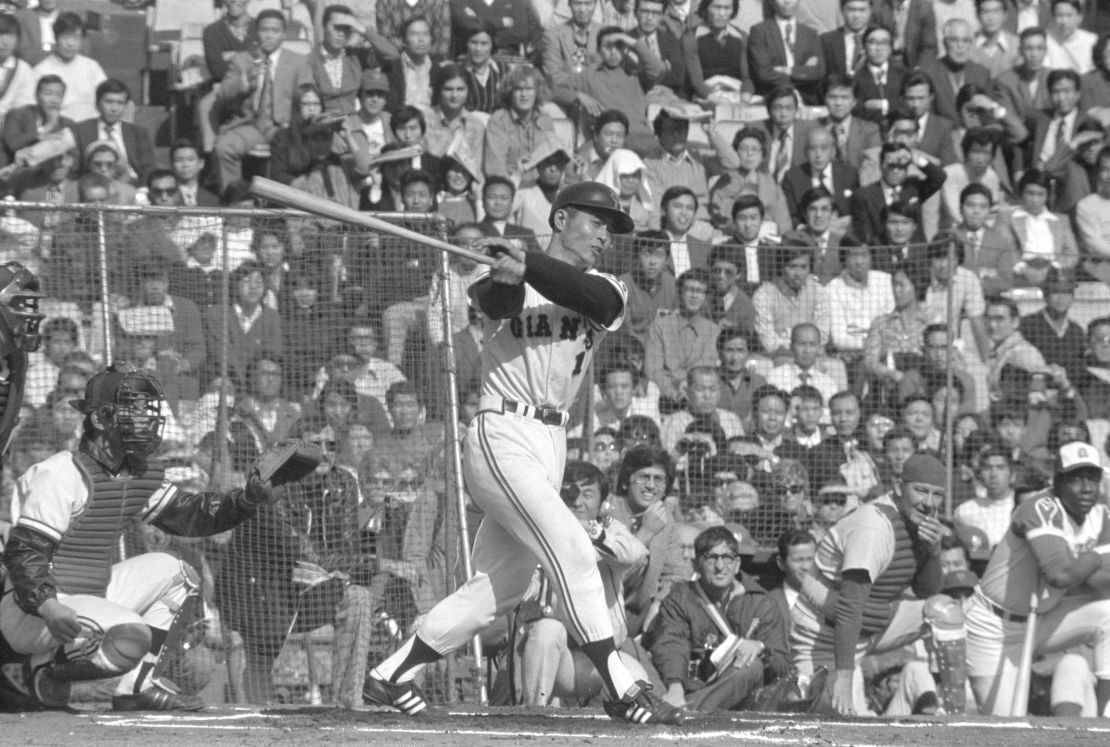

By then, Japan had established its own professional league, the Japanese Baseball League. In 1950, it was reorganized into Nippon Professional Baseball (NPB), and by the early 1960s, the sport had its first true superstars: Sadaharu Oh and Shigeo Nagashima.

“They were like the Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig of Japanese baseball,” Robert Whiting said of Sadaharu Oh and Shigeo Nagashima.

Oh was the bigger name—his 868 career home runs remain the most in professional baseball history, surpassing MLB record-holder Barry Bonds by more than 100. But when Whiting arrived in Japan in 1962, it was Nagashima who captivated the nation.

“You couldn’t walk down the street without seeing his face—on magazine covers, in bank advertisements, everywhere,” Whiting recalled. “Everybody knew Nagashima.”

His star power was undeniable. In the only professional baseball game ever attended by Emperor Hirohito, Nagashima delivered a performance for the ages, hitting two home runs, including a dramatic walk-off in the ninth inning.

“Many say that was the greatest game ever played in Japan,” Whiting said. “It was a huge moment.”

With Oh and Nagashima leading the way, the Yomiuri Giants—descended from the Japanese All-Stars who faced Babe Ruth’s touring team in 1934—dominated the sport, winning nine consecutive Japan Series championships from 1965 to 1973.

For Japan, it was a golden age of baseball. But in the U.S., the game’s smaller ballparks and perceived lower level of competition left many unconvinced of NPB’s greatness. That perception would change in 1995.

Across the Pacific

Hideo Nomo wasn’t the first Japanese player to compete in Major League Baseball—that distinction belongs to Masanori Murakami, who played for the San Francisco Giants in 1964 and 1965 as part of a cultural exchange program.

But Nomo’s impact was seismic. Named National League Rookie of the Year and an All-Star in 1995, he paved the way for the wave of Japanese talent that would reshape MLB over the next three decades.